Tight budgets, insufficiently-specific tools, and “we’ve always done it that way” thinking, sometimes lead towns and villages to underbuild their roads. But a road design that isn’t robust enough for the traffic it has to carry can lead to premature pavement failure and costly remediation. Photo: iStock

UTC partner David Orr, P.E., from the Cornell University Local Roads Program is working on a tool that will help local transportation agencies in charge of low-volume rural and local roads design and build them in keeping with the broad spectra of traffic loads they carry.

Tight budgets, insufficiently specific tools, and “we’ve always done it that way” thinking, sometimes lead towns and villages to underbuild their roads.

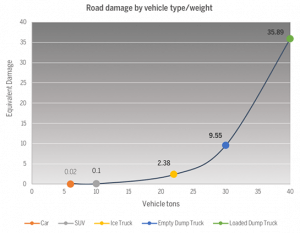

At $120,000 a lane-mile per inch of pavement for a typical town road, it’s not a cheap undertaking, and it’s easy to see the appeal of using a 3-inch lift versus a 4-inch lift. But a road design that isn’t robust enough for the traffic it has to carry can lead to premature pavement failure and costly remediation. “Saving on extra material and labor at the outset becomes penny-wise and pound-foolish if you have to tear it out and do it all over again halfway through the projected lifespan of the road,” Orr said.

Consider that 3.6 million heavy-duty Class 8 trucks move nearly 71 percent of all the freight tonnage in the United States. They do the vast majority of their traveling on larger highways and interstates, but there’s always that “last mile.” Last mile delivery is a term that, counterintuitively, actually can range from a few blocks to 50 or 100 miles. Local road officials need to consider that nearly 100 percent of last mile deliveries to their town’s commercial areas arrive by trucks with a gross vehicle weight rating from 14,000 to 33,300 pounds.

The tool that Orr is working on will help agencies design roads that meet the agency needs and pavement life-cycle cost expectations. Though the tool employs the same methods as laid out the Mechanistic-Empirical Pavement Design Guide, it will be much simpler and user friendly.

The tool that Orr is working on will help agencies design roads that meet the agency needs and pavement life-cycle cost expectations. Though the tool employs the same methods as laid out the Mechanistic-Empirical Pavement Design Guide, it will be much simpler and user friendly.

Initially it will be a spreadsheet-type tool, but Orr plans to evolve it into an app or nomograph that works with inputs that are both understandable and easily obtained by local agencies.

Orr explains, “For example, [local road managers] may need to take a core or test pit and get a sieve test and plasticity information, but would not need a more extensive resilient modulus test. The current thinking, from past experience and after talking with them, is the inputs [will likely include things like] current pavement thickness (layers), material type (asphalt, concrete, clean gravel, etc.), subgrade type, quality of drainage on site, total daily traffic and type (residential, commercial, agricultural, etc.) as well as anticipated traffic increases, and the expected lifespan of the new pavement or overlay.

“A draft of the model and a prototype of the user interface should be ready by the end of May. We have lined up local agencies to test the tool, hopefully starting in June. The final app or nomograph will be shaped by the needs and wants the local agencies express during the testing phase.

“We’re starting in New York State, but we think the model could easily be transferred to other states using already collected data on seasonal issues,” Orr said.

Working within the limited resources of small municipalities, this tool will help them make the best decisions in the interest of the traveling public and tax payers.

Orr did a presentation on this project, “When Should We Post Weight Limits,” at the 2018 Annual School for Highway Superintendents (Ithaca, NY) and the 2019 Association of Towns of the State of New York (New York City).

He also will be presenting at the upcoming TRB-sponsored 12th International Conference on Low-Volume Roads (Kalispell, MT) in September 2019, the proceedings of which will be published in Transportation Research Record.

May 2019