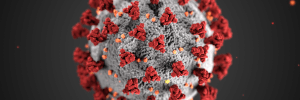

The impact of COVID-19, the novel Coronavirus, is being felt by everyone, with more than 750,000 confirmed cases globally, and 163,539 confirmed cases in the United States as of March 31. Photo ©U.S. Department of State.

These are unprecedented times as the Coronavirus, COVID-19, affects the world, the United States, and the Northeast region. Recent national numbers show New Jersey is second only to New York in cases of the virus, as its impact is felt everywhere through closed businesses, increased social distancing measures, online classes, and more. CAIT-affiliated researcher Dr. James W. Hughes breaks down what some of the longer-term economic and transportation-related effects of the virus might be on the region. He cautions that unrelenting changes occurring on a daily basis place sharp limits on the shelf life of any future forecast, so caution is warranted.

A few weeks after New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy’s executive order directing residents to stay at home and closing all non-essential businesses due to the novel Coronavirus, COVID-19, what has become clear is that these are unprecedented times and the situation is changing rapidly.

The Northeast region has been hit hard by the virus, with more than 18,696 confirmed cases in New Jersey alone as of March 31. Business outside of healthcare and essential parts of the food industry have shut down, and Dr. James W. Hughes, a university professor and dean emeritus of Rutgers’ Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy and affiliated researcher at the Center for Advanced Infrastructure and Transportation (CAIT), said there is no way to avoid at least a short-term recession as a result. Large swaths of the economy have just been shut down—an economic equivalent of a medically-induced coma is still unfolding.

Dr. James W. Hughes is a nationally known expert on demographics, housing and regional economics. Photo ©Rutgers University.

“We are in an unprecedented situation,” Dr. Hughes said. “Right now it is hard to say exactly what might happen, but many forecasts are projecting a ‘V-shaped’ recession and recovery—the question being how steep and deep the ‘V’ will get.”

A typical V-shaped recession would mean a sharp decline in economic activity in the 2nd quarter and then an equivalent sharp bounce back potentially in the 3rd quarter if the virus were to run its course by then. People would return to work as the shut-down economy reboots, he explained. A more negative outcome would be if the effects of the virus were to last longer, halting production in the 2nd, 3rd, or 4th quarters—or remaining flat—before a bounce back. That would be a U-shaped downturn and recovery.

This means the region would be negatively impacted for an extended period of time, he said—the likes of which could have future structural implications too.

“We tend to divide economic change into either cyclical or structural,” he said. “Cyclical relates to the short-term impact of business cycle shifts, while structural change means a more profound, long-lasting permanency has taken place.”

For example, typically cyclical change would mean that unemployed people who are recession casualties cannot afford to eat out so the restaurant business contracts, but once people are re-employed, the restaurants should bounce back. Of course, the mandatory short-term restrictions currently in effect amplify this cyclical impact. In contrast, virus-induced structural changes to the region’s economy would result from permanent changes in people’s’ behavior—people might start thinking differently about going out to restaurants and being in such close proximity to others. Millennials in particular have been at the forefront of the emergence of the new experiential economy–preferring to purchase experiences (such as travel and group activities) rather than goods. But will the health dangers of the experiential way of life that the virus has exposed produce different economic protocols?

On the transportation side, structural changes could have a significant impact too.

“Are policies going to change at the national level to limit dependence on the global supply chains as a result of this?” Dr. Hughes said. Will this increase suburbanization—as the benefit of having more space and a backyard might become emphasized during this crisis? And, how would that impact how people and goods move? Structural change could potentially redefine all types of transportation flows, but we will have to wait and see exactly how the virus and recovery unfolds.”

Here is how the virus is impacting some other aspects of transportation in the region, and what that could mean for the future.

Transportation Investment

Home to nearly 10 percent of the population and jobs in the United States, the Northeast region is one of the busiest and most densely-populated areas across the country. NJDOT estimates that the state moves over 450 million tons of goods per year by truck.

To meet the commerce, supply chain, and travel needs, the region has developed a diverse transportation system that, unfortunately, includes some of the oldest infrastructure in the country. Investing in this infrastructure has to be a priority in order to maintain it and to meet ever-increasing and changing demands.

Dr. Hughes said that transportation investment has always been an economic stimulant. It is an area with bipartisan support in the nation’s capital.

“In trying to jumpstart the economy, a lot of the federal spending is going to evolve over time, with the immediate rescue helping households making sure people can pay bills, and keeping businesses from collapsing,” he said. “But longer term, infrastructure investment will be needed. New Jersey’s strongest periods of economic growth followed massive transformations of transportation systems.”

He said the state had some of the first toll roads in the country, and that investment in transportation really drove the economy in the 1950s, 60s, 70s, and 80s, highlighting the opportunity for—eventually—new federal funding.

Agencies

Federal funding will also help out some of the state’s big public transportation agencies such as PANYNJ, NJ Transit, the New Jersey Turnpike and Amtrak, he said.

That patronage and revenue dimensions of these sectors have been badly hit, he said. The question is—how substantial is the federal legislation going to be to avoid permanent harm or layoffs?

“Obviously, journey-to-work trips are down outside of food shopping,” he said. “A small counterbalance is in delivery services and truck deliveries, which have increased flows. But, overall, it is safe to say that transportation movements will be down for the time being and congestion has already been put on hold.”

Global Supply Chains

New Jersey is the third largest warehouse distribution logistics market in the country and as global supply chains continue to be disrupted, that breakdown may be felt locally too, Dr. Hughes said.

“So far, globally interconnected supply chains have been disrupted,” he said. “Goods that we depend on are not flowing in from China. The extension of that is the question of what will be coming into New Jersey’s air and seaports if there is a restructuring of extant supply chains?”

He expects that the broader region will see some shifts there as well as if fundamental logistical changes unfold.

“We have never been through anything like this before,” Dr. Hughes said. “Hopefully, we will have a V-shaped recession and recovery, and the impacts will not be too severe so that region will be able to return to normal sooner rather than later. Unfortunately, the worst is still yet to come. Statistically, governmental economic performance metrics that will be released during the next several months will set negative records before the rebound begins. What is unknown is whether there will be a ‘new’ normal when the economy finally achieves recovery.”