Using drones equipped with high-quality cameras, researchers were able to inspect different interchanges. Photo ©Michael O’Connell.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) can potentially collect and inventory high-quality interchange asset data in a safer, faster, and smarter way than traditional on-the-ground surveys.

Safety and innovation are two of four goals that the United States Department of Transportation (USDOT) identified in its FY 2018-2022 Strategic Plan. By leveraging drone data that was collected under a related CAIT UTC research project in a new way, researchers are able to inspect interchanges for Wrong-Way Driving (WWD) crash vulnerabilities.

On and off ramps connect freeways and highways to local roads. When a driver mistakenly enters a freeway from an exit ramp, called Wrong-Way Driving, it creates a high-danger situation. These incidents have long been a critical safety issue for transportation agencies.

A collaborative project between the Rutgers Center for Advanced Infrastructure and Transportation (CAIT), Rowan University, and other universities, “Application of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles to Inspect and Inventory Interchange Assets to Mitigate Wrong-Way Entries,” explored using drones to collect high-quality data from exit-ramps regarding these crashes. It found that when equipped with cameras, drones can be used to inspect and inventory exit-ramp assets to gather information and learn more about the causes of WWD collisions.

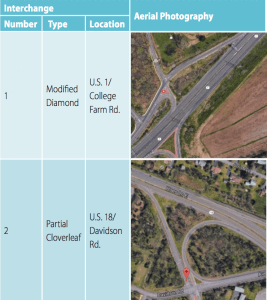

The interchange at U.S. Route 1 and College Farm Road, and U.S. Route 18 and Davidson Road in New Jersey were evaluated.

The study was just featured in the July 2019 edition of the Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE) Journal, which is distributed to more than 14,000 ITE members.

Dr. Mohammad Jalayer, lead author on the study and an assistant professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Rowan University, said that the study is a step toward adopting drones for transportation research and safety practices.

“Traditional methods of collecting WWD data are time consuming and expose crews to traffic hazards,” Jalayer said. “We showed here that drones have the potential to collect accurate data in a faster, safer, and more efficient way—all of which could help in reducing WWD crashes and accomplishing the ‘Toward Zero Deaths’ goal of many transportation stakeholders in the future.”

Other researchers involved included Michael O’Connell, a research associate at CAIT; Dr. Huaguo Zhou, a professor in the Department of Civil Engineering at Auburn University; Dr. Patrick Szary, associate director of CAIT; and Dr. Subasish Das, an associate transportation researcher with the Texas A&M Transportation Institute.

“These are high-speed head-on collisions,” Szary said. “For this reason, people involved in WWD crashes are much more likely to die than people involved in other types of crashes.”

According to data from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS) database, in 2018 there were 598 WWD crashes in New Jersey, which caused 215 serious injuries and 13 fatalities. In 2017, 618 WWD crashes were counted resulting in 200 serious injuries and 7 fatalities.

There are many reasons why WWD incidents occur including driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs, fatigue, or confusing roadway signs and design. In this project, the research team focused on gathering information about that last variable: confusing signs, pavement markings, or designs on exit-ramp terminals.

They started by creating a list of common features associated with exit-ramp terminals and WWD crashes. These include the presence of “Do Not Enter” signs, “Wrong-Way Arrow” pavement markings, and raised curb medians. Researchers also examined the condition of these features. With this information, they developed a Wrong-Way Entry Checklist that acts as a tool for ranking an exit-ramp in terms of its signs, pavement markings, or design features.

Two interchanges were evaluated during this study. At the end, researchers used data collected from the drones to fill out checklists and document the exit ramps.

“Wrong-Way” signs and other interchange assets were captured by the drones and evaluated. Photo ©Michael O’Connell.

Results show that in one of the interchanges there were no “Wrong-Way Arrows,” other markings such as stopping lines at the end of exit ramps, or design features in place to prevent vehicles from driving the wrong way on the exit ramp. At the other interchange, there were no “Do Not Enter” signs, other markings, or design features to prevent drivers from going the wrong way.

Jalayer said a lack of information to guide drivers at these locations is a missed preventative measure against WWD incidents.

“Past studies have shown that exit-ramp terminals are the most common location for drivers to enter a highway going the wrong direction,” he said. “If we do not have the proper signs or features, the risk of a WWD crash could increase.”

O’Connell said that UAVs have a lot of safety applications. In this case, they can safely gather data about exit ramps that can be used to quickly inform stakeholders.

“Given the rapid expansion of drone technology, UAVs are likely to play a key role in addressing this important issue as well as many other safety concerns,” he said. “Field surveys are time-consuming, labor-intensive, and sometimes hazardous. Investing in drone technology and expanding this research to larger test locations can save time, money, and improve safety.”