A new Rutgers Regional Report documents the rise of international migration as a primary demographic engine of growth as the result of a region suffering from sustained domestic out-migration. As demographic changes impact the workforce and movement of people and goods, it might also shape the larger transportation network.

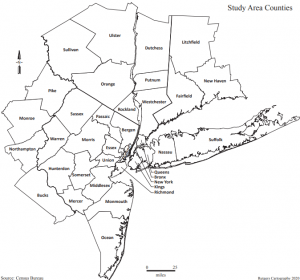

The Four-State (Connecticut, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania) 35-County Metropolitan Region. Photo ©Rutgers Regional Report.

A hot topic in the news these days, immigration has become a polarizing issue. Clickbait headlines aside, understanding these trends is important for understanding how the Northeast is developing – and being prepared for it from a planning, transportation, or policy perspective.

Imagine what property taxes might look like if people were not buying homes left vacant by those leaving the region – on the other hand, that notion might be at odds with the very success of the regional core as an influx of people could drive up livability costs. While the final outcomes of these different dynamics are unclear, discussing them can help regional stakeholders make informed decisions. According to the Rutgers Regional Report, these dynamics have become a significant factor in the Northeast as new data shows domestic outmigration and international immigration impacting its demographic makeup.

Between April 1, 2010 and July 1, 2018, the four-state, 35-county metropolitan region encompassing New Jersey, New York, Connecticut and Pennsylvania lost 1.4 million people due to net domestic out-migration.

That is a net loss of 469 people per day, 3,282 per week and 171,137 per year as a result of more people moving out of the region than into it during this period without accounting for international migration.

The region has recently slipped into absolute population decline, and one of two major counterforces forestalling a demographic catastrophe has been positive international migration. During that same time period, the region’s net international migration gains totaled 935,084 people, or 310 people per day, 2,172 people per week and 113,278 people per year.

These findings and more are documented In the forty-first Rutgers Regional Report, “Urbs,” “Burbs,” and the Immigration Locomotive: An Analysis of Economic, Demographic and Market Trends. The report was produced by Dr. James W. Hughes, a university professor and dean emeritus of Rutgers’ Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy; Rutgers alumnus Connie O. Hughes, former Chief of Management and Policy in the NJ Governor’s Office; and Dr. Joseph J. Seneca, a university professor emeritus. It was published by the Rutgers Center for Advanced Infrastructure and Transportation (CAIT),

While this inflow from international migration is still approximately one-half million less than total domestic losses, without it the region would have had to deal with multiple repercussions and a struggle to remain economically competitive, the researchers said. Population losses of that scale would entail significant income and tax revenue losses, as well as cause labor force shortages that would inhibit the competitiveness and growth of the region’s economy.

“Immigration has become the primary source of population stability in our region—the demographic locomotive,” Dr. Hughes said. “Without it, the region would have to bear fully the economic consequences of what has become a virtual domestic population hemorrhage—a vast exodus of regional residents moving to the rest of the country. This is just one dimension of endemic demographic change that has swept the post–Great Recession world.”

New immigrant populations are increasingly driving change in the broader transportation world too.

“Urbs,” “Burbs,” and the Immigration Locomotive: An Analysis of Economic, Demographic and Market Trends was co-produced by Dr. James W. Hughes and published by Rutgers CAIT. Photo ©Rutgers Regional Report.

Dr. Hughes said that new populations create new patterns of need and demand. For example, public transit will continue to play a vital role particularly for the newest and most recent arrivals. He also said that the travel behavior of these populations will not be fixed, but will evolve as they will probably “transport assimilate” over time.

Labor is another area of change.

There is a general labor shortage, in the region and well as nationally, and all transportation organizations will become increasingly dependent on this new source of workers to maintain efficiency and effectiveness, Dr. Hughes said.

The report goes on to discuss the other ameliorating force at hand, net natural increase (births minus deaths), which increased by 908,203 people in the region during that same time period. The authors said that while these net gains surmounted the overall net migration losses, producing overall population growth, net natural increase has much less of an immediate impact in the short term on the size of the adult population or the available workforce.

The dispersion of people immigrating to the United States during this time period, and new patterns of dispersion between urban and suburban areas, were also discussed and analyzed in the report.

The previous report, the 30th annual Rutgers Regional Report, “Move Over Millennials: New Jersey’s Unfolding Generational Disruptions,” was also authored by Dr. Hughes and Dr. Seneca. It recently exceeded 3,000 downloads through the Scholarly Open Access at Rutgers database.

That report traces demographic changes in New Jersey through six generations: pre-baby boomers (born before 1946), baby boomers, Generation X, millennials, Generation Z, and Generation Alpha (born after 2012).

“New immigrant populations are now the largest population growth sector, and they are a force in reshaping the regional population geography,” Dr. Hughes said. “In a region that is losing substantial numbers of existing residents and workers to other parts of the country, understanding these demographic trends and how they can impact the region is vitally important.”